by Mackenzie Mulligan –

by Mackenzie Mulligan –

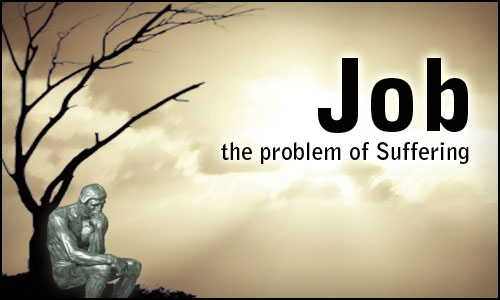

That is the question for the ages. The suffering of bad people, of evil people, is (for some) an easier question. There is a notion of cosmic reparation, whether of impersonal karma or personal Justice, that provides an explanation on that front. But what of good people?

That, at least, is a question asked repeatedly by characters in G. K. Chesterton’s The Man who was Thursday, and the answers Chesterton hints at are some of the most incredible I have ever read.

But first, we must eliminate the greatest of the false trails apologists often stray down: that human goodness is never good enough in comparison to Christ’s perfection. This relativity, while actual, is nonetheless irrelevant. The goodness and righteousness even of fallen humanity is real enough and meaningful enough to be attested to even from the throne of Jehovah himself. I trust ye have heard of the patience of Job?

The question, therefore, is not one of goodness. Any answer which depends on any concept of “deserving” is no answer at all, but merely a dodge—a dodge in the finest tradition of miserable comforters and worthless physicians the world over.

Having avoided the dodge, we return to Chesterton, who illuminates a facet of theodicy that I have never before and never again seen illuminated so clearly and eloquently:

Why does each thing on the earth war against each other thing? Why does each small thing in the world have to fight against the world itself? … So that each thing that obeys law may have the glory and isolation of the anarchist. So that each man fighting for order may be as brave and good a man as the dynamiter. So that the real lie of Satan may be flung back in the face of this blasphemer, so that by tears and torture we may earn the right to say to this man, ‘You lie!’ No agonies can be too great to buy the right to say to this accuser, ‘We also have suffered.’

This is what I have long thought of as the “theodicy of glory.” Without adversity, there can be no perseverance, only the potential for perseverance. Without overwhelming odds, there can be no valor. Without fear, there can be no bravery.

And without these things, each and every believer is subject to the great accusation that begins the conflict in Job. Without these things, we are unproven, untested, and even Satan himself could rightly claim to have persevered through suffering, while we ourselves could not. Without this, all the saints are open to the accusation that they loved God merely because they were safe, and not for any other reason.

Why do the people of God often feel alone? Why do they often suffer? Why do they, at times, seem to fight against the entire world?

So that they may stand firm despite their loneliness. So that they may remain resolute in their suffering. So that they may feel the same distress and pain as those who reject God, yet emerge victorious.

And by this, by their blood and sweat and tears, the people of God may earn the right to say with pride, “I have fought the good fight, though armies were against me. I have finished the race, though terrible obstacles stood in my path. And I have kept the faith, though the world itself tried to take it from me.”

Well done, good and faithful servant.

Having passed through the fire and emerged triumphant, the saints will take no heed of the Accuser, for his talk is meaningless. And at the end, they will receive their crown of righteousness from nail-scarred hands and hear the voice which echoed from the cross of Calvary say, “Well done, good and faithful servant.”

Thursday is, in many important ways, a parallel of the book of Job, and this is as far as the story of Job takes us. Thursday, however, goes further. Job (and Thursday himself) are thus free from the accusation of safeness and surety and happiness. But to Chesterton, the final piece of the puzzle is found when God—the same God who spoke out of the whirlwind in power and majesty—places himself on the cross and refuses to come down. In this way God himself puts the Accuser forever to shame, and proves that he is God and he is Good even when he is not safe, even when he is not happy.

And while this may not always put my reason at ease, I can say, along with Thursday, that it puts my heart and soul at ease.